It was announced this week that Poverty Reduction has been officially removed from the goals of Australia’s foreign aid. Many people have asked, quite fairly I think, if reducing poerty is not the goal of foreign aid, then what is? There are some possibly good answers to that question, but my fear is that the real answer is either self-interest, economics or politics (which may or may not all be one and the same).

Now perhaps it is naive and idealistic of me to think that it has ever been any way but thus. After last year’s election, the new federal government changed the status of AUSAid from a separate agency to part of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which seems a fairly clear indication that our aid goals are subservient to our political or diplomatic ones. It has recently emerged that our previous government gave specific amounts of aid to certain countries as “incentives” for votes to secure us a UN Security Council seat, which also makes a fairly blatant statement about our priorities.

It seems to me that the government knows that most people won’t care and will just accept that this is of course the ways things work. That a government’s role is always political before it is humanitarian. However, I find the priorities this reflects, and the assumptions it makes about what our community wants, quite frightening.

This week I also listened to a radio interview with the Premier and Opposition Leader in the leadup to our state election. They were asked about their plan for the state, and both gave answers solely about the economy. Now, I don’t want to deny that economics is important, but the assumption that economy = state is similarly one that I find problematic.

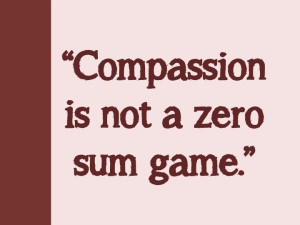

Surely there is more to what it means to be a community than how much revenue we can generate. Surely life is not valued in dollar terms alone. Surely we look for more in a government than simply who can make us have the most money in our pocket, like for starters, perhaps, oh I don’t know, … maybe who can govern well?!

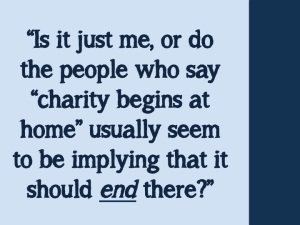

Both these examples seem to be symptoms of a wider issue, where political decisions are being made on the twin assumptions that money is the only indicator of success, and that self-interest is the only motivation for people to act.

As a follower of Jesus, I do not share those assumptions and priorities. I follow the life and teachings of a Man who says, “Love your enemies, do good, lend, expecting nothing in return“(Luke 6:37-38) and “It is more blessed to give than to receive.” (Acts 20:35)

But I’d also challenge those in my community who do not share my Christian faith to consider whether those assumptions really reflect the kind of nation they want us to be. When we strip away the details and debates and niceties, is that really a bottom line we are comfortable standing for?

I am reminded again of a question asked by my favourite fictional politician, one which caused him to reflect on his assumptions and actions. The context is a conversation with one of his staffers about foreign aid, and aid in particular to the fictional nation of Equatorial Kundu.

President Bartlet: Why is a Kundunese life worth less to me than an American life?

Will Bailey: I don’t know, sir, but it is.

The West Wing, Episode 4 x 15, Inuguration: Over There

I worry that in Australia today not only does it seem we are unwilling to consider the answers to those kind of questions, but that apparently it doesn’t even occur to us to think of asking them.